Ghosts of Thanksgivings past

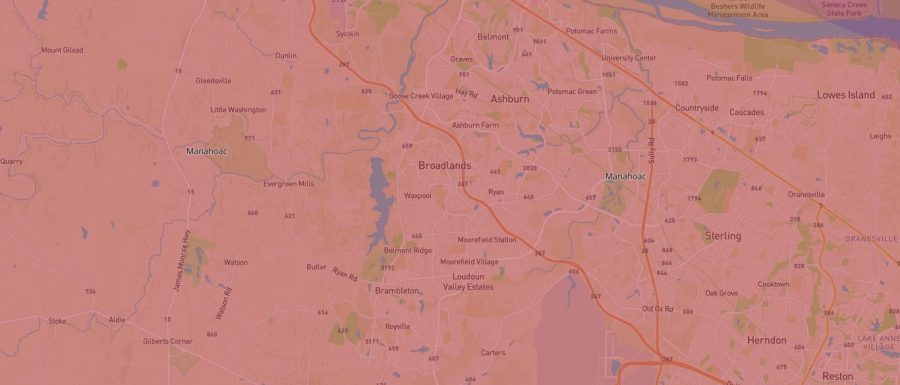

This interactive map, run by nonprofit organization Native Land Digital, shows approximately what tribe lived on any given region of land. Depicted here is Ashburn; years earlier, it had be inhabited by the Manahoac tribe, according to the map.

Legions of roast turkey, platters of mashed potatoes, boats of gravy and cranberry sauce: Every year, Americans around the nation celebrate Thanksgiving, the commemoration of the colonial pilgrims’ first harvest in 1621. Since then, it has come to represent bountiful crops, the gathering of family and the peaceful partnership between settlers and Native Americans.

But there is a growing faction of Americans who are beginning to recognize the other repercussions of that bloody legacy. In 1970, the United American Indians of New England (UAINE) recognized Thanksgiving as a day of mourning. Today, they use it as a way to literally and figuratively protest the broad narrative most commonly recognized in the American imagination. “Four hundred years after the arrival of the Mayflower, Indigenous people are still denied the respect and lands that are theirs by right,” said UAINE’s youth coordinator Kisha James. “The Mashpee Wampanoag continue to have their lands threatened even in the final days of the Trump administration. Change is long past due.”

Years ago, James’ grandfather, Wamsutta Frank James, wrote a Thanksgiving speech for the annual march, which he was ultimately barred from giving. “We, the Wampanoags, will help you celebrate in the concept of a new beginning. It was the beginning of a new life for the Pilgrims,” he wrote. “Now, 350 years later, it is the beginning of a new determination for the original American, the American Indian.”

The UAINE are not the only people who push for wider recognition of the human toll of the holiday. “I call Thanksgiving ‘Colonists’ day,’” said senior Gia Annunziata, with a laugh. “But it’s frustrating.”

Annunziata, who is part-Chippewa through her mother, recounted some of her early experiences as a child. “When I was younger, [students] would ask if I lived in a teepee — those people would assume that everyone who was Native American had to live on a reservation. My friends wouldn’t believe me when I said I was Native American. They would ask me, ‘Why don’t you live with the other Native Americans?’”

Annunziata pointed to the American education system as a major factor behind that ignorance pertaining to the fate of countless Native Americans throughout history, much of which the U.S. government perpetuated. “Even at my old school… when they would teach about Native Americans, they weren’t giving the best picture of them. They were showing us as weak, like when the colonists came over and massacred everyone and they took the land. They were just unempathetic about it,” she said. “The most education people get is from the school system, which doesn’t even give that much information on Native Americans.”

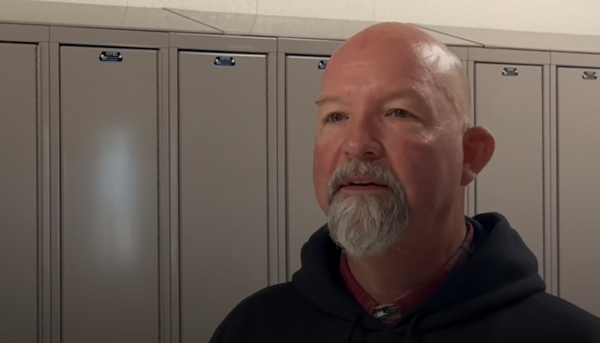

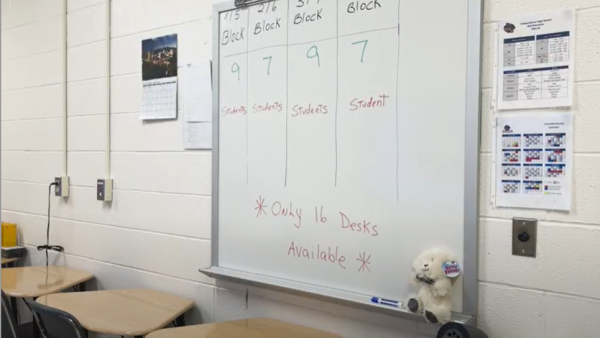

Dr. Brian Miller, of the social sciences department, noted that the education system tends to reinforce the insulation surrounding Native Americans in the classroom, saying that unless mainstream America could feel the direct effects of the situation, very little would change. “The history books are that way too. They talk a little bit about it with John Smith, Pocahontas, and then it’s just gone… It’s these politicians making these choices which narrows down the history. You have to pick and choose [what to include], and they tend to always choose on the side of American exceptionalism, which is why most history books don’t show the Native American genocide.”

Miller also emphasized the importance of covering such controversial topics. “It’s important to understand the situation that we [Americans] are in… not necessarily that we should be running around feeling guilty today about the transgressions of the past and our ancestors, but we should acknowledge that it happened and try to help these groups out because it did happen,” he said. “There’s enough resources out there to learn about the history of those nations, [and] those people. But we get in these trends; it’s not that people are being purposefully ignorant, it’s just that this is the way it always was and therefore this is the way it’s always gonna be.”